Get the lowdown on how much you should be drinking for your mileage

One glance at the queues for pre-race portable toilets at any big run is all the evidence you need to prove that the importance of hydration has been well drummed into runners. In fact, runners are so diligent about what they drink that the over-reliance on single-use plastic bottles at big events is now getting a lot of attention.

All the chat about good drinking habits is for a good reason. Bad hydration impairs your performance, hampers your enjoyment and in extreme cases can be dangerous.

- Essential reading: The best electrolytes and hydration for runners

But there’s more to optimal hydration than just chugging down litres of water. Kieran Alger, a man who has run multi-day ultras in the mountains as well as desert races including the Marathon Des Sables, covers everything you need to know about topping up fluids properly so you can perform at your best, wherever you’re running.

How to spot dehydration

Let’s start with how you know if you’re dehydrated. By far the most accurate method is a blood test but drawing claret pre or mid-run isn’t particularly practical. Luckily there are a few simple alternatives you can use to spot when you need more fluids.

Are you thirsty?

The obvious one is thirst. That’s your brain’s way of telling you you’re running low and you need to take on fluids.

Drinking to thirst is something many experts recommend, however, one recent study by the University of Arkansas has cast doubts on this as an effective method of managing hydration for athletes.

By the time thirst strikes, you’re already dehydrated and some of the side effects will have already started to impair performance. If you’re in the marginal gains world of running for performance, you might wish to avoid that.

What colour is your pee?

Another method is the so-called pee test, based on the Armstrong Chart, a paint swatch-style colour chart with eight different gradations from a rather worrying green, through to pale yellow.

If your urine is in the light straw to pale yellow colour you’re in good shape. If you’re in darker or green territory it’s time to drink. If there’s a lack of volume in your pee and a strong smell too, that can also be a sign of dehydration – or that you ate asparagus or beetroot.

Again, though, while this might be useful before a run or on ultras where there’s time for pit stops, it’s not so practical during a marathon where you won’t want to be stopping for a wee to check.

Could technology have the answer?

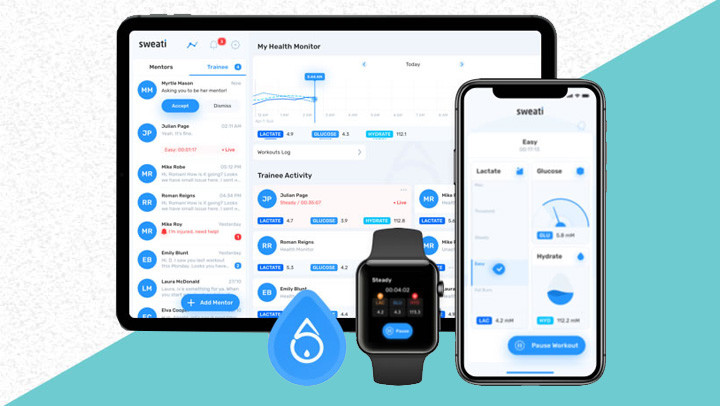

In the not too distant future, technology might be able to tell us with reasonable accuracy when we’re at risk of dehydration.

At least two companies are working sensor-laden patches that can read your hydration levels in real time. Sweati uses your sweat as a proxy for blood to check for dehydration while Gatorade is developing similar technology.

How dehydration hampers your running

Dehydration affects you mentally and physically and studies have shown that just 5% dehydration can result in up to a 30% reduction in performance. To put that into context, if you were chasing a sub-3 hour marathon, that level of dehydration could add an extra hour to your finish time.

When you’re dehydrated, your blood volume decreases requiring your heart to work harder to get the blood to the muscles. Studies have shown it also reduces aerobic endurance performance and results in increased body temperature, heart rate and perceived exertion, and can possibly lead to an increased reliance on carbohydrate as a fuel source. Not to mention upping the likelihood of muscle cramps, nausea and fatigue.

The importance of electrolytes

Despite what Instagram claims, sweat isn’t weakness leaking out. It’s actually a combination of water, lipids, urea and salts, aka electrolytes. These electrolytes are crucial for the body as they regulate blood pressure, nerve and muscle function and keep your pH balance. Having the right amount of these salts in the blood also affects the body’s ability to absorb fluids.

The main electrolytes include sodium, calcium, potassium, chloride and magnesium and they all work in a careful balance. When you’re looking for an electrolyte solution it’s important to consider the levels of sodium, particularly as this is one of the most important for hydration.

Are you drinking the right tonics?

Not all drinks are created equal and the rate at which your choice of sports or electrolyte drink enters the bloodstream depends on the concentration of the fluids.

Hypotonic drinks: These have low levels of carbohydrates and a lower concentration than blood. They offer the quickest way to get fluids and salts into the bloodstream. If hydration is your number one goal, this is what you need.

Isotonic drinks: Higher in carbs, these drinks like Lucozade Sport and Gatorade have a similar concentration to blood but take longer to move through the gut wall, so energy and electrolyte release is slower. Often used for a supply of energy and hydration where there’s less of an instant need for fluids.

Hypertonic drinks: These have a higher concentration than blood and are much higher in carbohydrates than the other two options. They take the longest to enter the system and are mainly used to fuel or as recovery drinks.

Is it possible to pre-hydrate?

In short, yes. NASA studies have shown that it’s possible to pre-hydrate and increase blood volume. The smart way to approach this in the build-up to the race, rather than leaving it to the last minute to smash three litres of water on race morning. That’ll only have you rushing for that portable toilet queue.

Add some electrolytes to your water in the days building up to the race with a focus on what you drink the afternoon and early evening before. Then on the morning of the race sip a 500-650ml bottle of electrolyte solution with breakfast and on the way to the race.

How much should I drink during my run?

This will vary from person to person depending on genetics, height and weight, not to mention how far, fast and the climate you’re running in. And more isn’t always better, in fact over-drinking can be deadly.

For a 5k or up to 30 minutes: If you’re pretty good at getting fluids into your daily routine, then your normal consumption of liquids should be ample to see you round your parkrun. Unless you’ve been on the sauce the night before or you’re looking to break the parkrun world record, in which case taking an optimal approach to hydration might mean paying a little more attention to your pre-hydration.

For a 10k or up to 60 minutes: If you’ve pre-hydrated well and you can knock out a 10km in under an hour, in most cases topping up with a few mouthfuls of water every 10-15 minutes should be sufficient for a 10km.

For a half and full marathon: According to The International Marathon Medical Directors Association during a marathon, runners should drink about 400-800ml of fluid per hour, though the top end of that limit is recommended for warmer environments and for faster and heavier runners.

Carrying hydration

Well organised half marathons and marathons have aid stations offering water at regular intervals so in most cases there are enough fluids on offer that you don’t need to bring your own.

However, there are benefits to carrying some fluids, particularly if adding a little extra weight isn’t going to really affect your time. For a start, you can drink when you need to and not when the aid station arrives. You can also run through busy aid stations and crucially, you can add electrolytes to the mix in your bottles.

For marathons and half marathons, there are plenty of minimal hydration belts that you’ll barely notice. For ultras, it’s worth looking at a hydration belt with bigger bottles, either solid or soft flask, or considering a Camelbak-style hydration pouch.

For our full guide on the best hydration packs click here.